ON THE HIDDEN COSTS OF NFTS

Non-fungible tokens - NFTs - are the hot topic when it comes to the modern digital art market. Hot as in trendy, and hot as in a significant driver for global warming.

NFTs are unique files that are able to verify ownership of a work of digital art. The major marketplaces for NFT art conduct their sales through Ethereum, a decentralised blockchain network, which maintains a secure record of cryptocurrency and NFT transactions, and is upheld through a process called mining. This system involves a network of computers that use advanced cryptography to decide whether transactions are valid and to keep blockchain records coherent. Running all this computational power uses energy on the scale of a small country and, while translating this energy consumption to carbon emissions is difficult, the sheer scale of energy use should get us thinking - what’s the use of allocating any at all for crypto art?

We’ve seen the way digital art has been pirated in the past and we all remember the ‘You wouldn’t steal a car’ anti-piracy ad, but that didn’t really stop people from downloading movies and music albums, did it?

So what is the ultimate point of owning an NFT? While anyone can see and easily screenshot the world’s first tweet (which was sold for 2.9 million USD), they would have to purchase the individual, impossible-to-pirate, limited-edition NFT version if they wanted the distinction of owning the original, collectable version. These ownership certificates usually give buyers limited rights to display the digital artwork they represent, but in reality these are no more than bragging rights.

The world’s first tweet (complementary)

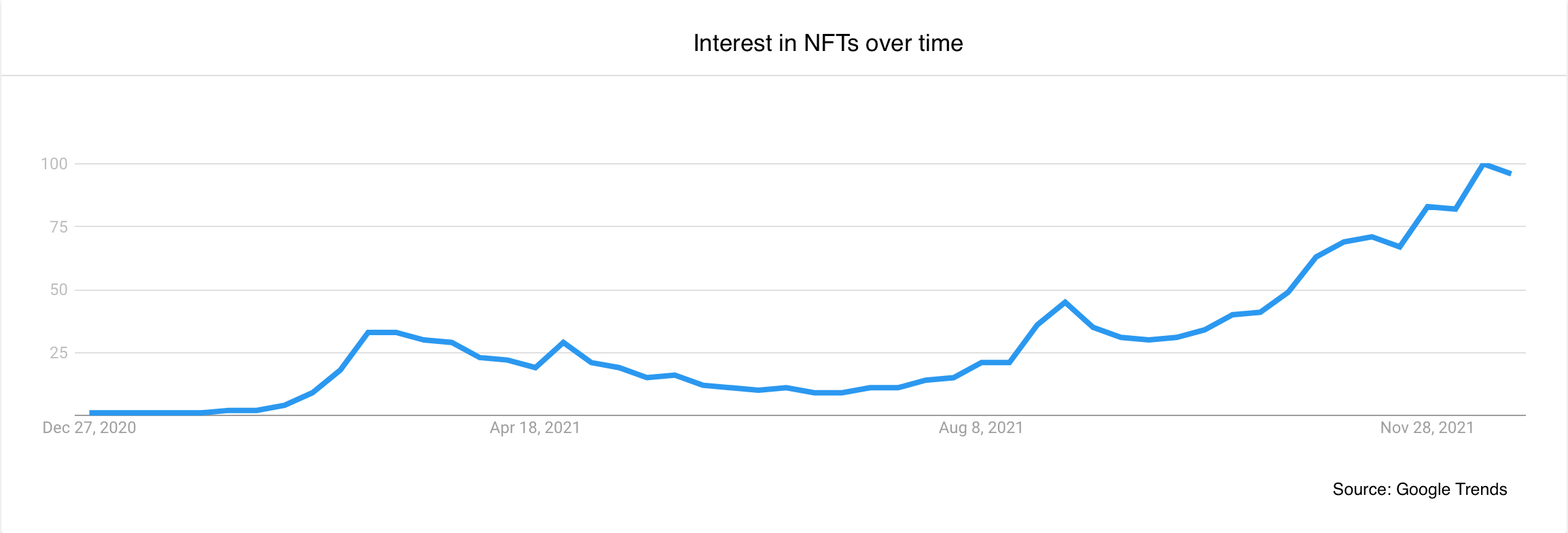

People might argue that if someone is willing to pay that much money for an ownership token then that’s fair game and nobody else’s business. But if this NFT frenzy is feeding on a resource-heavy technology for the sake of questionable art ownership, doesn’t it concern us all? When an NFT is sold there is a seamless transaction in the digital world that translates to a very real and large energy spend in the physical world, and because of hype-driven markets, these artworks are then re-sold over and over again - a trend not predicted to stop anytime soon.

The stories of artists becoming millionaires overnight (which are far rarer than the internet wants you to believe), the ethical and environmental concerns behind NFTs and all the current hype around them make these ‘digital receipts’ as divisive as they are popular. But where do they add value in this world besides to someone’s bank account?

Take Brian Eno, a ‘would be’ perfect artist for the NFT era, having spent decades intertwining technology and its social implications in his practice as well as building a huge fan base along the way. But instead of joining the craze and effortlessly banking a few million pounds, Eno has decided to keep away from this market, convinced NFTs are pointless as an artistic move and craven as a financial one:

“NFTs seem to me just a way for artists to get a little piece of the action from global capitalism, our own cute little version of financialization. How sweet — now artists can become little capitalist assholes as well.”

Brian Eno for the Crypto Syllabus

The discussion on NFTs is far from over, and while NFTs didn’t have all this ethical and environmental baggage attached to them back when they first started in 2014, their quick rise to internet fame brings a lot of questions that demand answers before artists blindly jump in to get a piece of the $$$ action.